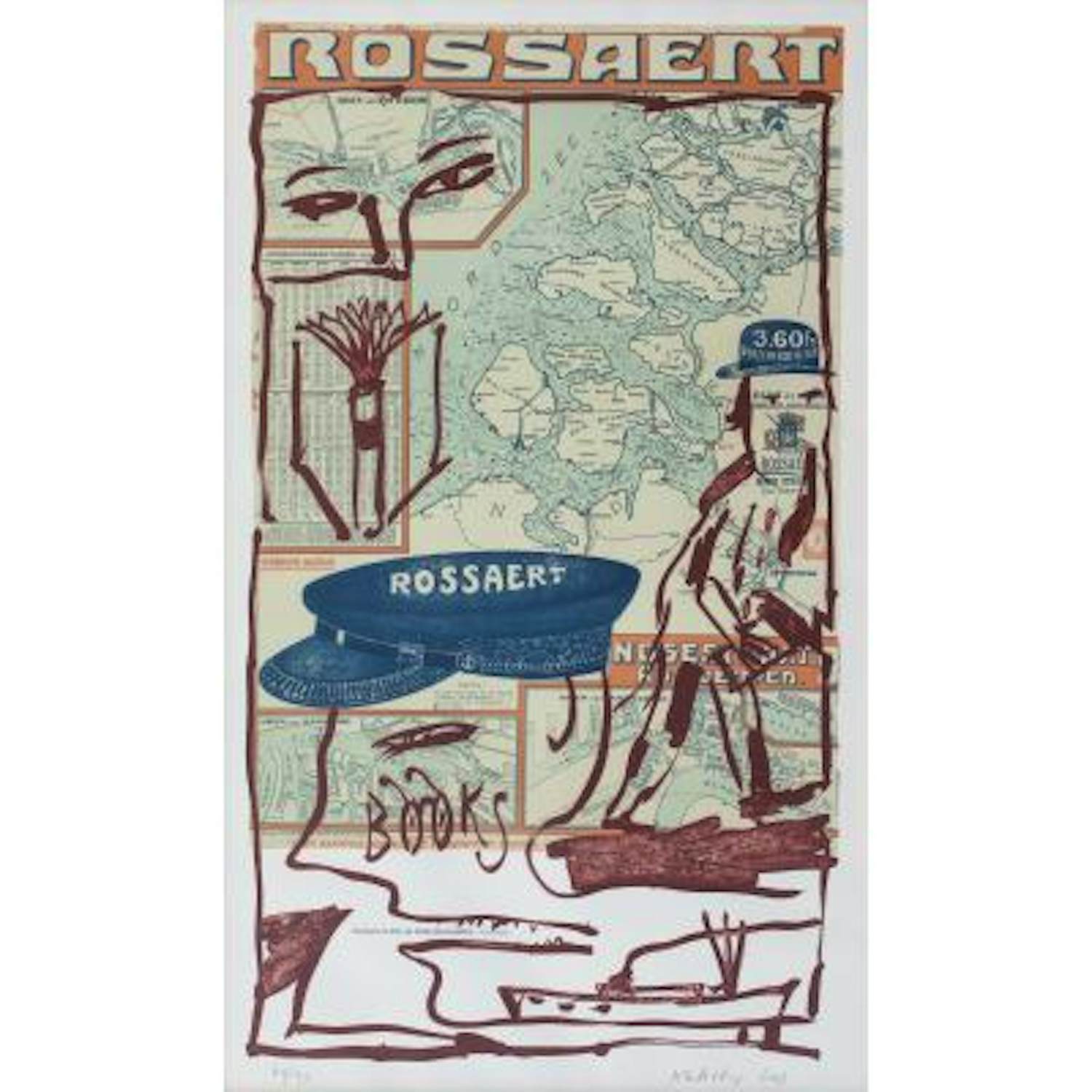

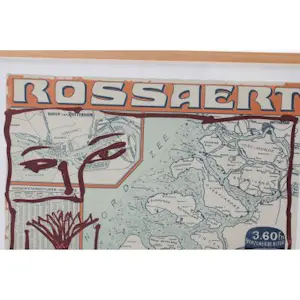

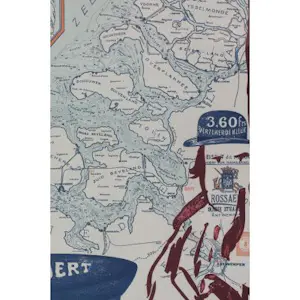

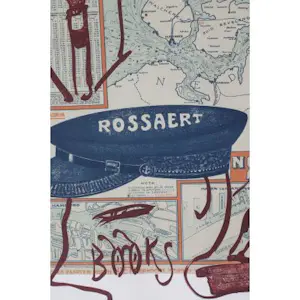

Pierre Alechinsky - Rossaert

- Description

- Pierre Alechinsky (1927)

| Type of artwork | Prints (signed) |

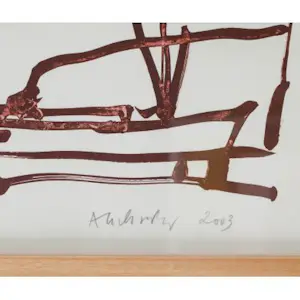

| Year | 2003 |

| Technique | Lithograph |

| Support | Paper |

| Style | Abstract |

| Subject | Abstract |

| Framed | Framed |

| Dimensions | 93.5 x 55 cm (h x w) |

| Incl. frame | 98 x 59 cm (h x w) |

| Signed | Hand signed |

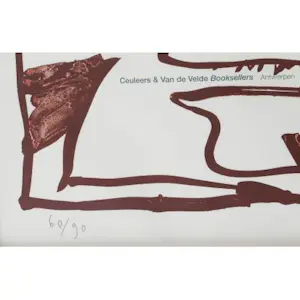

| Edition | 60/90 |

Translated with Google Translate. Original text show .

Pierre Alechinsky (Saint-Gilles, Brussels, 19 October 1927) is a Belgian painter and graphic artist.

To live

From 1944 to 1948, Alechinsky studied applied graphic arts, (book) illustration, typography, and photography at the École nationale supérieure des arts visuals (ENSAV), formerly the École nationale supérieure d'Architecture et des Arts décoratifs (ENSAAD - la Cambre) (Ter Kameren) in Brussels. In 1945, he discovered the work of Henri Michaux and Jean Dubuffet and developed a friendship with the art critic Jacques Putman, who dedicated several works to Alechinsky. In 1947, he began his painting career and joined De Jonge Belgische Schilderkunst (The Young Belgian Painters) and also had his first solo exhibition in Brussels.

On November 8, 1948, the artist group Cobra was founded in Paris. Alechinsky discovered this group during a visit to the international exhibition of experimental art 'La fin et les moyens' in Brussels in March 1949 and immediately became a member.[1] Along with Christian Dotremont, Alechinsky was the driving force behind the Belgian section of Cobra. Along with the sculptors Olivier Strebelle and Reinhoud, he also organized the community center 'Les ateliers du Marais', which was a meeting place for many Cobra artists. He participated in both Cobra exhibitions, in 1949 and 1951. In 1950, he received the "Jeune Peinture Belge" Prize.

The last one, held in Liège, was even organized by Alechinsky. However, during this period, he was so busy organizing various Cobra events and editing the Cobra movement's magazine that he produced very little himself. His output only really picked up after Cobra's dissolution.

In 1951, Alechinsky left for Paris to study engraving and printing techniques with Stanley William Hayter at Atelier 17. From 1951 onward, his work leaned toward Expressionism, having previously been primarily influenced by Surrealism. In Paris, he became acquainted with artists such as Alberto Giacometti, Bram van Velde, and Asger Jorn. In 1954, he had his first exhibition in Paris at the Nina Dausset Gallery. During the first half of the 1950s, his work became increasingly free, and abstract accents can be seen in the lines.

In 1954, Alechinsky came into contact with Chinese painting through the Chinese painter Walasse Ting, who would strongly influence his work. Besides the Chinese influence, Japanese art also had a significant impact. He also began to show an interest in Eastern calligraphy. This is evident in the documentary film "Calligraphie japonaise," which he shot in Kyoto in 1955. He began painting on large sheets of paper laid out on the floor. From 1952 onwards, he maintained a correspondence with the Japanese calligrapher Shiryu Morita. In this way, Alechinsky attempted to bridge the gap between Eastern and Western art.

His international fame grew steadily. Alechinsky had his first major exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts in Brussels in 1955. He also had exhibitions in London (1958), at the Kunsthalle Bern (1959), at the 1960 Venice Biennale in the Belgian Pavilion, in Pittsburgh and at the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam in 1961, in New York, and at Silkeborg in Denmark (1963). From the 1960s to the present, numerous exhibitions have been dedicated to Alechinsky's work worldwide. In 2000, the PMMK in Ostend honored him with a retrospective. In 1999 and 2002, Micky and Pierre Alechinsky were guests of honor at the then-gallery space and "Rossaert" building of art dealer Ronny Van de Velde in Antwerp. Painter-photographer Guy Donkers portrayed the painters Pierre Alechinsky and Walasse Ting there together in 1999. From late 2007 to the spring of 2008, the Royal Museum of Fine Arts of Belgium (RMFAB) in Brussels dedicated a retrospective to the work of Pierre Alechinsky, who was then honored for his eightieth birthday and his achievements as a multidisciplinary artist.

In 1963, he moved his studio to Bougival, near Paris, where André Breton came to visit him. In 1965, he took part in the last major surrealist exhibition, L'Ecart Absolu, in Paris at the Galerie de l'Oeil. In 1969, he organized a retrospective exhibition in Brussels. In it, he convincingly demonstrated that, although his work retains a fundamental affinity with that of Jorn, Alechinsky nevertheless managed to acquire a personal language and style in the post-Cobra period.[1] In 1977, Alechinsky was awarded the Andrew W. Mellon Prize for his contribution to modern art. In 1983, he became professor of painting at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris.

In 1994, he received an honorary doctorate from the Vrije Universiteit Brussel. Impressions of Alechinsky's works were featured on Belgian postage stamps in 1995 and 2012. The French postal service also issued stamps featuring his work in 1985 and again in 1992. The French stamps are like fine works of art in themselves, printed using a refined printing technique (the tactile lines of etching).

On the occasion of his eightieth birthday in 2007, the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium in Brussels paid tribute to him with a retrospective exhibition of his 60-year career.

Alechinsky is also active as a writer. His writings were collected in The Other Hand, translated by Hugo Claus and Freddy De Vree.

Work

Alechinsky combined several techniques in his work, such as watercolor and sketching. His work became more dynamic in the latter half of the 1950s. He also applied his paint increasingly thickly to the canvas. His canvases were covered with masses of paint in shades of green, blue, white, and gray. Thus, in the late 1950s, his work achieved greater freedom (in both form and color), and mythical creatures also appear in his works.

Karel J. Geirlandt wrote the following about Alechinsky's art in his extensive article:

What are the characteristics of his art? First of all, a handwriting that moves across the canvas like a gadfly against a stained-glass window. The line determines the flow of events and confirms the priority of the drawing. Alechinsky is an exceptional draftsman who, with brush or quill and ink, performs wonders of drawing and narrative. There is something of a cartoonist in him and a master of writing mischievous and playful short stories. Titles like "I remember very well," "Go fetch me a box of matches," "As if it were so important," "Dude, I never say it any other way," that's all abstract painting, "Write the word lion" point to his humor and his Latin predilection for witticisms, jeu de mots, calembour, saillie, quid pro quo, etc. Naturally, the ink of the writing becomes the chosen medium for drawing, just as from the predilection for drawing arises the desire "to paint as I draw." His ink paintings on crumpled Paper is among the most delightful in his oeuvre. Ink and color are linked in his evocation of "Violet: Memories of School. The inkwell level with the edge of the desk, its smell, its dirt." Incidentally: Alechinsky is left-handed; he learned to write with his right hand at school. Is drawing the revenge of the left hand on the clumsy handwriting of the right? A comment by Alechinsky convinces us of the joy drawing brings him: "A blot, a line reveals itself as a monster, with its mouth wide open and a tongue that turns into a piece of calligraphy."[1]

In 1955, Alechinsky stayed in Japan and studied calligraphy. He even filmed it. What struck him most was their posture while working. From then on, he would lay paper or canvas on the floor and work while hunched over the work. This allowed his arm and hand to be completely free and free in their movements. Another characteristic of his work is the "goose-board" composition. In it, the figures crowd into the curves of the meandering line. They spread across the entire surface or, as in his latest works, surround a central drawing. Finally, the Ensor palette is typical. These are the thin layers of paint and his transparent and fresh colors. Geirlandt also wrote: "This commentary has emphasized the playful nature of the work. Yet it would be an injustice to Alechinsky to limit his oeuvre to this. The dramatic and the comic are intertwined in the grotesque art of today, which is a mirror image of modern man, 'a sinnliches Paradox, namely the shape of an unnatural form, the face of a visually incomprehensible world'."[2][1]

In 1965, he switched from oil to acrylic painting, combining it with paper that he later marouflages onto canvas. Incidentally, he participated in the last Surrealist exhibition with his first acrylic painting, "Central Park." From that moment on, he also introduced his characteristic "drawn frames": series of drawings arranged around the central work as if it were a comic strip, with the core, the subject, in the center, acting as the front cover. In some works, this frame even became more important than the title page. Several of his works no longer even have a title page: they are collages of dozens of drawings.

Also noteworthy—from the late 1980s onward—is the introduction of manhole covers into his work. Armed with paper, he would go out into the street and make a "copy" of the cover (just as we, as children, would copy a coin on paper with a pencil), around which he would then play and improvise.

Works in public collections (selection)

Rijksmuseum Amsterdam[3]

The Last Day, 1964, oil on canvas, 306 x 506 x 8 cm, Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp, inv. no. 3039.

The Sad Dragon, acrylic on canvas, 152 x 114 cm, Museum of Fine Arts (Liège)

The Cobra Museum Amstelveen (exhibition in 2016-2017 and some works on loan)

The work "Sept écritures" hangs in the entrance hall of the Delta metro station in Brussels. This work, created in collaboration with Christian Dotremont, hung in Anneessens station from 1976 to 2006.

Source: https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pierre_Alechinsky

To live

From 1944 to 1948, Alechinsky studied applied graphic arts, (book) illustration, typography, and photography at the École nationale supérieure des arts visuals (ENSAV), formerly the École nationale supérieure d'Architecture et des Arts décoratifs (ENSAAD - la Cambre) (Ter Kameren) in Brussels. In 1945, he discovered the work of Henri Michaux and Jean Dubuffet and developed a friendship with the art critic Jacques Putman, who dedicated several works to Alechinsky. In 1947, he began his painting career and joined De Jonge Belgische Schilderkunst (The Young Belgian Painters) and also had his first solo exhibition in Brussels.

On November 8, 1948, the artist group Cobra was founded in Paris. Alechinsky discovered this group during a visit to the international exhibition of experimental art 'La fin et les moyens' in Brussels in March 1949 and immediately became a member.[1] Along with Christian Dotremont, Alechinsky was the driving force behind the Belgian section of Cobra. Along with the sculptors Olivier Strebelle and Reinhoud, he also organized the community center 'Les ateliers du Marais', which was a meeting place for many Cobra artists. He participated in both Cobra exhibitions, in 1949 and 1951. In 1950, he received the "Jeune Peinture Belge" Prize.

The last one, held in Liège, was even organized by Alechinsky. However, during this period, he was so busy organizing various Cobra events and editing the Cobra movement's magazine that he produced very little himself. His output only really picked up after Cobra's dissolution.

In 1951, Alechinsky left for Paris to study engraving and printing techniques with Stanley William Hayter at Atelier 17. From 1951 onward, his work leaned toward Expressionism, having previously been primarily influenced by Surrealism. In Paris, he became acquainted with artists such as Alberto Giacometti, Bram van Velde, and Asger Jorn. In 1954, he had his first exhibition in Paris at the Nina Dausset Gallery. During the first half of the 1950s, his work became increasingly free, and abstract accents can be seen in the lines.

In 1954, Alechinsky came into contact with Chinese painting through the Chinese painter Walasse Ting, who would strongly influence his work. Besides the Chinese influence, Japanese art also had a significant impact. He also began to show an interest in Eastern calligraphy. This is evident in the documentary film "Calligraphie japonaise," which he shot in Kyoto in 1955. He began painting on large sheets of paper laid out on the floor. From 1952 onwards, he maintained a correspondence with the Japanese calligrapher Shiryu Morita. In this way, Alechinsky attempted to bridge the gap between Eastern and Western art.

His international fame grew steadily. Alechinsky had his first major exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts in Brussels in 1955. He also had exhibitions in London (1958), at the Kunsthalle Bern (1959), at the 1960 Venice Biennale in the Belgian Pavilion, in Pittsburgh and at the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam in 1961, in New York, and at Silkeborg in Denmark (1963). From the 1960s to the present, numerous exhibitions have been dedicated to Alechinsky's work worldwide. In 2000, the PMMK in Ostend honored him with a retrospective. In 1999 and 2002, Micky and Pierre Alechinsky were guests of honor at the then-gallery space and "Rossaert" building of art dealer Ronny Van de Velde in Antwerp. Painter-photographer Guy Donkers portrayed the painters Pierre Alechinsky and Walasse Ting there together in 1999. From late 2007 to the spring of 2008, the Royal Museum of Fine Arts of Belgium (RMFAB) in Brussels dedicated a retrospective to the work of Pierre Alechinsky, who was then honored for his eightieth birthday and his achievements as a multidisciplinary artist.

In 1963, he moved his studio to Bougival, near Paris, where André Breton came to visit him. In 1965, he took part in the last major surrealist exhibition, L'Ecart Absolu, in Paris at the Galerie de l'Oeil. In 1969, he organized a retrospective exhibition in Brussels. In it, he convincingly demonstrated that, although his work retains a fundamental affinity with that of Jorn, Alechinsky nevertheless managed to acquire a personal language and style in the post-Cobra period.[1] In 1977, Alechinsky was awarded the Andrew W. Mellon Prize for his contribution to modern art. In 1983, he became professor of painting at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris.

In 1994, he received an honorary doctorate from the Vrije Universiteit Brussel. Impressions of Alechinsky's works were featured on Belgian postage stamps in 1995 and 2012. The French postal service also issued stamps featuring his work in 1985 and again in 1992. The French stamps are like fine works of art in themselves, printed using a refined printing technique (the tactile lines of etching).

On the occasion of his eightieth birthday in 2007, the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium in Brussels paid tribute to him with a retrospective exhibition of his 60-year career.

Alechinsky is also active as a writer. His writings were collected in The Other Hand, translated by Hugo Claus and Freddy De Vree.

Work

Alechinsky combined several techniques in his work, such as watercolor and sketching. His work became more dynamic in the latter half of the 1950s. He also applied his paint increasingly thickly to the canvas. His canvases were covered with masses of paint in shades of green, blue, white, and gray. Thus, in the late 1950s, his work achieved greater freedom (in both form and color), and mythical creatures also appear in his works.

Karel J. Geirlandt wrote the following about Alechinsky's art in his extensive article:

What are the characteristics of his art? First of all, a handwriting that moves across the canvas like a gadfly against a stained-glass window. The line determines the flow of events and confirms the priority of the drawing. Alechinsky is an exceptional draftsman who, with brush or quill and ink, performs wonders of drawing and narrative. There is something of a cartoonist in him and a master of writing mischievous and playful short stories. Titles like "I remember very well," "Go fetch me a box of matches," "As if it were so important," "Dude, I never say it any other way," that's all abstract painting, "Write the word lion" point to his humor and his Latin predilection for witticisms, jeu de mots, calembour, saillie, quid pro quo, etc. Naturally, the ink of the writing becomes the chosen medium for drawing, just as from the predilection for drawing arises the desire "to paint as I draw." His ink paintings on crumpled Paper is among the most delightful in his oeuvre. Ink and color are linked in his evocation of "Violet: Memories of School. The inkwell level with the edge of the desk, its smell, its dirt." Incidentally: Alechinsky is left-handed; he learned to write with his right hand at school. Is drawing the revenge of the left hand on the clumsy handwriting of the right? A comment by Alechinsky convinces us of the joy drawing brings him: "A blot, a line reveals itself as a monster, with its mouth wide open and a tongue that turns into a piece of calligraphy."[1]

In 1955, Alechinsky stayed in Japan and studied calligraphy. He even filmed it. What struck him most was their posture while working. From then on, he would lay paper or canvas on the floor and work while hunched over the work. This allowed his arm and hand to be completely free and free in their movements. Another characteristic of his work is the "goose-board" composition. In it, the figures crowd into the curves of the meandering line. They spread across the entire surface or, as in his latest works, surround a central drawing. Finally, the Ensor palette is typical. These are the thin layers of paint and his transparent and fresh colors. Geirlandt also wrote: "This commentary has emphasized the playful nature of the work. Yet it would be an injustice to Alechinsky to limit his oeuvre to this. The dramatic and the comic are intertwined in the grotesque art of today, which is a mirror image of modern man, 'a sinnliches Paradox, namely the shape of an unnatural form, the face of a visually incomprehensible world'."[2][1]

In 1965, he switched from oil to acrylic painting, combining it with paper that he later marouflages onto canvas. Incidentally, he participated in the last Surrealist exhibition with his first acrylic painting, "Central Park." From that moment on, he also introduced his characteristic "drawn frames": series of drawings arranged around the central work as if it were a comic strip, with the core, the subject, in the center, acting as the front cover. In some works, this frame even became more important than the title page. Several of his works no longer even have a title page: they are collages of dozens of drawings.

Also noteworthy—from the late 1980s onward—is the introduction of manhole covers into his work. Armed with paper, he would go out into the street and make a "copy" of the cover (just as we, as children, would copy a coin on paper with a pencil), around which he would then play and improvise.

Works in public collections (selection)

Rijksmuseum Amsterdam[3]

The Last Day, 1964, oil on canvas, 306 x 506 x 8 cm, Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp, inv. no. 3039.

The Sad Dragon, acrylic on canvas, 152 x 114 cm, Museum of Fine Arts (Liège)

The Cobra Museum Amstelveen (exhibition in 2016-2017 and some works on loan)

The work "Sept écritures" hangs in the entrance hall of the Delta metro station in Brussels. This work, created in collaboration with Christian Dotremont, hung in Anneessens station from 1976 to 2006.

Source: https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pierre_Alechinsky

| Condition | |

| Condition | Very good |

| see photos | |

| Shipment | |

| Pick up | The work can be picked up on location. As a buyer you must bring your own packaging materials. The location is: Antwerpen-historisch stadscentrum, Belgium |

| Shipment | Due to its size or fragility, it is not possible to send this item via regular mail |

| Guarantee | |

| Guarantee | By putting the item up for auction, I agree with the Terms of Guarantee as they are applicable at Kunstveiling regarding the accuracy of the description of the item |

The seller takes full responsibility for this item. Kunstveiling only provides the platform to facilitate this transaction, which has to be settled directly with the seller. More information .

Belgian

Belgian